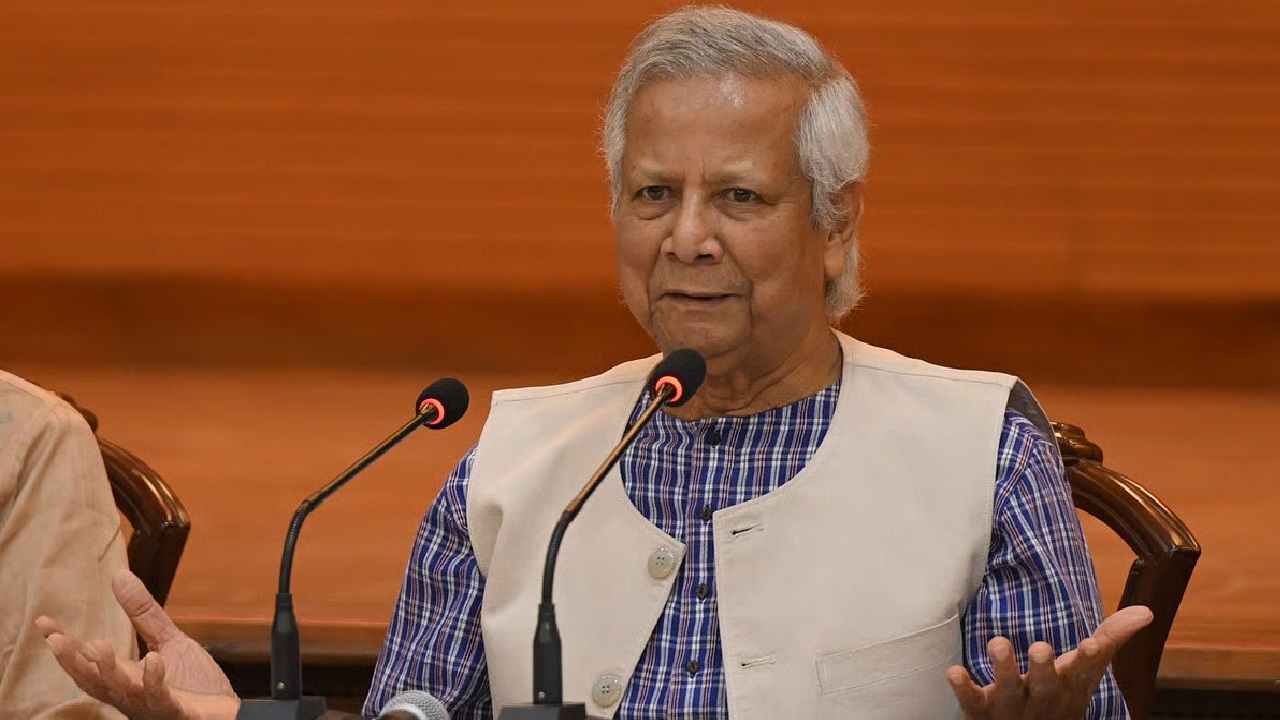

A Fractured Mandate: Yunus Considers Stepping Down

Bangladesh’s interim government chief, Professor Muhammad Yunus, is contemplating resignation, citing his inability to operate amid deep political divisions. The revelation, confirmed by National Citizen Party (NCP) chief Nhid Islam in a statement to BBC Bangla, underscores a mounting crisis in the post-uprising transitional administration.

“We have been hearing news of Sir’s resignation since this morning,” Islam said. “He said he is thinking about it… the situation is such that he cannot work.” Yunus, a Nobel laureate and a figurehead of Bangladesh’s brief moment of technocratic hope, now stands at a crossroads.

From Protest to Power: How Yunus Rose to Lead

Muhammad Yunus came to power under extraordinary circumstances. His appointment as the interim chief adviser followed the collapse of Sheikh Hasina’s government in the wake of a sweeping student-led uprising. The movement, spearheaded by Students Against Discrimination (SAD), erupted over corruption, nepotism, and political gridlock.

Hasina’s Awami League regime fell after military forces, rather than suppressing protests, facilitated her safe departure to India. In a rare moment of strategic restraint, the military refrained from using force and instead supported a civilian transition. Yunus, viewed as a neutral and reform-minded leader, was installed as a compromise figure — a nod to both protesters and a wary establishment.

The Illusion of Consensus: Political Gridlock Grips Dhaka

Despite initial hopes, Yunus’s interim government has foundered. His mission — to oversee reforms and prepare the country for fresh democratic elections — has been stymied by the very political forces he was meant to mediate.

Bangladesh’s entrenched party rivalries, primarily between the Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), have re-emerged with renewed intensity. Talks have failed to produce any meaningful agreement on a roadmap forward, leaving the interim administration isolated.

According to NCP leader Nhid Islam, Yunus feels his efforts are futile without a consensus: “I won’t be able to work unless the political parties can reach a common ground.” This lack of unity not only hampers governance but risks reigniting instability.

The NCP, born out of the protest movement and viewed by many as Yunus’s informal support base, has pleaded with him to stay. Islam emphasized the symbolic weight of Yunus’s leadership for a country still reeling from upheaval: “I told him to stay strong for the sake of the country’s security and future.”

Yet, even Islam concedes the futility of symbolic leadership without operational authority: “Why should he stay if he does not get that place of trust, that place of assurance?”

Power, Protest, and the Military’s Quiet Role

One of the least acknowledged but most influential players in this drama remains Bangladesh’s military. During last year’s protests, the army chose to stand down — a decision that paved the way for Hasina’s ouster and Yunus’s rise.

This strategic neutrality gave the military moral legitimacy in the eyes of many citizens. But recent tensions suggest their patience is wearing thin. Though not overtly assertive, the military’s posture now appears more skeptical than supportive.

If Yunus resigns, it’s unclear whether civilian forces can manage a peaceful transition or if the military might step in to “stabilize” the situation once more — an ominous possibility in a country with a long history of coups and martial rule.

A Nation at an Uncertain Crossroads

Professor Yunus’s possible resignation reflects more than a personal dilemma — it captures the profound challenges of transitional governance in a polarized, post-authoritarian context. His appointment was supposed to be a reset, a bridge between the past and a reimagined political future. Instead, he’s ensnared in the same cycles of distrust that brought his predecessors down.

Bangladesh, in the absence of unity or reform, risks sliding back into a familiar chaos. If Yunus steps aside, the country may lose its last remaining figure of consensus. The question then becomes: who, or what, fills the vacuum?

(With agency inputs)