India Is Not a Dharamshala, Says Supreme Court

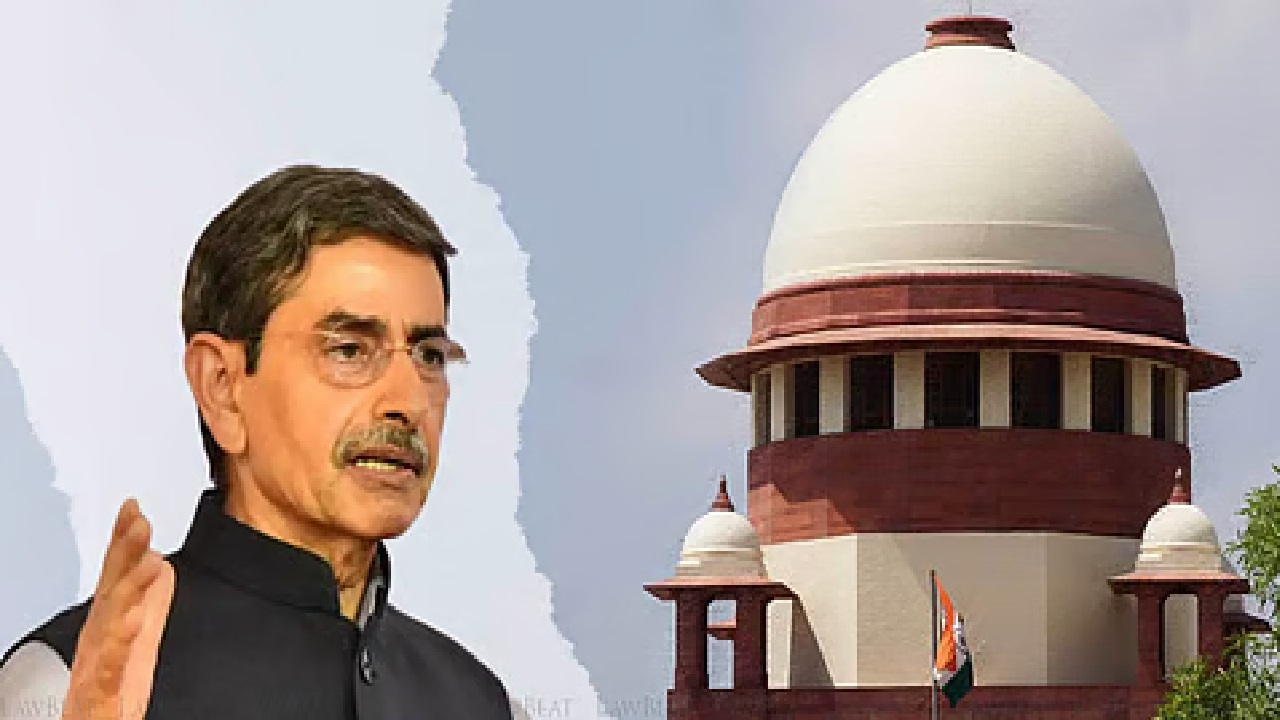

Reinforcing the country’s sovereign right to control immigration and its asylum policy, the Supreme Court of India recently declined a plea by a Sri Lankan national seeking refuge, invoking a stark analogy: “India is not a dharamshala (free shelter) that can entertain refugees from all over the world.”

The comment was made by a bench comprising Justice Dipankar Datta and Justice K Vinod Chandran while hearing a plea by a Sri Lankan man formerly associated with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a banned terrorist organisation. Arrested in 2015 and later convicted under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), the man had completed his sentence and sought to remain in India, citing threats to his life in his home country.

From Conviction to Refugee Plea

The petitioner, a Sri Lankan national, entered India legally on a valid visa but was arrested in 2015 on suspicion of being linked to LTTE. In 2018, a trial court found him guilty under the UAPA and sentenced him to 10 years in prison. This was later reduced to 7 years by the Madras High Court in 2022, which also directed his deportation following completion of the sentence. Until then, he was to be kept in a refugee camp.

However, the deportation process had not commenced even after his release. He subsequently approached the Supreme Court, claiming that returning to Sri Lanka posed a threat to his life. He also informed the court that his wife and children were residing in India, adding a humanitarian dimension to his plea.

The Legal Argument: Fundamental Rights vs. National Security

The petitioner’s counsel based his argument on Articles 21 and 19 of the Indian Constitution. Article 21 guarantees the right to life and personal liberty to all persons, not just Indian citizens. Article 19, however, applies specifically to Indian citizens and provides rights such as freedom of speech, movement, and residence.

The bench, while acknowledging Article 21’s universal application, noted that the petitioner’s detention was lawful and therefore did not violate his right to life. As for Article 19, the court firmly pointed out that it holds no relevance for a foreign national seeking settlement in India. Justice Datta’s pointed question, “What is your right to settle here?”, underscored the court’s stance that residency in India is not a matter of entitlement for foreign nationals.

Asylum, Sovereignty, and the Indian Legal Framework

India, unlike many Western nations, is not a signatory to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol. As a result, there is no domestic legal framework that obligates the Indian state to grant asylum. Decisions on refugee matters are made administratively, on a case-by-case basis, often influenced by diplomatic, security, and humanitarian considerations.

India has historically hosted large numbers of refugees—from Tibet, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, and Myanmar—but always as a matter of policy, not obligation. In this context, the court’s assertion about India not being a “dharamshala” must be understood as a reaffirmation of the discretionary nature of refugee accommodation, particularly in cases where national security is implicated.

Wider Implications: Drawing the Line Between Compassion and Caution

The case highlights a critical balancing act between humanitarian concerns and national interest. On one hand, the petitioner presented a legitimate fear of persecution. On the other, his association with a proscribed organisation and his legal history placed him under scrutiny.

The ruling sets a precedent that while India remains compassionate, especially to those fleeing genuine persecution, that compassion does not translate into an unregulated open-door policy. Citizenship and long-term residency rights remain privileges governed by law, not sentiments.

Sovereignty Comes First

In dismissing the plea, the Supreme Court has drawn a clear line: India cannot be compelled to become a haven for all displaced individuals, especially those with a criminal past or affiliations with extremist groups. The message is unambiguous — India reserves the right to decide who stays within its borders, guided by both legal reasoning and national interest.

While the humanitarian angle of family ties and personal risk cannot be ignored, the verdict underscores a principle vital to any sovereign state — the right to control its demographic and security landscape. In doing so, the court has not closed the doors to genuine refugees, but it has reaffirmed that India is not a shelter without rules.

(With agency inputs)