The Quiet Creek with High Stakes

Amid the vast salt marshes of the Rann of Kutch, a seemingly unremarkable tidal estuary has held the power to trigger diplomatic clashes and military alerts for over seven decades. This is Sir Creek—a 96-kilometre-long strip of water that empties into the Arabian Sea. While appearing desolate, the creek is a geopolitical flashpoint. It defines part of the sensitive India–Pakistan border and influences claims over vast maritime zones rich in energy resources.

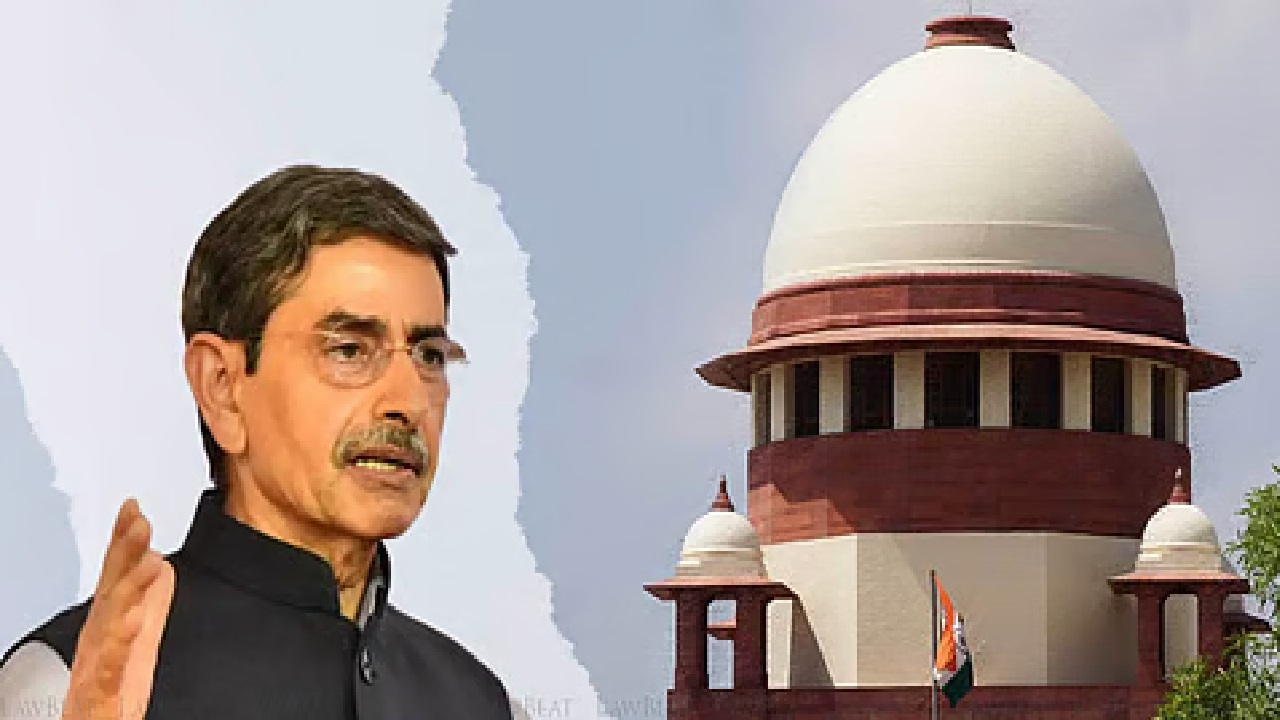

For India, Sir Creek is more than a boundary dispute. It is about protecting sovereignty, securing maritime rights, ensuring coastal security, and safeguarding the livelihoods of thousands of fishermen. The dispute resurfaced sharply when Defence Minister Rajnath Singh delivered a direct warning to Pakistan during his visit to Gujarat’s Kutch, declaring that any misadventure in the creek region would be met with a response “so strong that both history and geography would be changed.”

Historical Roots of the Dispute

The origins of the Sir Creek conflict trace back to colonial India. In 1908, a quarrel between the rulers of Kutch and Sind over a pile of firewood spiralled into a larger border question. The British issued a resolution in 1914, but ambiguity remained.

After independence, tensions flared again. Pakistan staked claims along the 24th parallel in the Rann of Kutch during the 1960s, while India argued for a boundary further north. Following skirmishes in 1965, the dispute was referred to an international tribunal. In 1968, the tribunal awarded nearly 90 percent of the territory to India, with minor concessions to Pakistan—but Sir Creek was left unresolved.

At the heart of the disagreement lies interpretation: Pakistan insists the eastern bank defines the boundary, granting it control over the entire channel, while India argues that the thalweg principle—the mid-channel line used in navigable waters—should apply. India backs its stance with 1925 maps and physical markers; Pakistan counters that the principle applies to rivers, not tidal estuaries. The creek’s shifting course adds further complexity.

Why Sir Creek Matters Today

Though militarily limited, Sir Creek carries huge economic and strategic weight. Control of the estuary shapes the maritime boundary and determines the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extending 200 nautical miles into the Arabian Sea. Whoever prevails gains access to potential reserves of oil and gas.

Fisheries add another layer of sensitivity. Thousands of fishermen from Gujarat and Sindh rely on these waters, but without a clear border, they often drift into disputed zones. Harsh tidal currents make it impossible for small boats to judge boundaries, resulting in frequent arrests. Crews languish in jails for years, while their confiscated boats devastate families economically.

Rising Militarisation of the Creek

In recent years, Pakistan has stepped up its presence in the region, raising new Creek Battalions, deploying marine assault craft, and reinforcing air defences with radars and missiles. Additional naval posts and surveillance infrastructure signal an attempt to consolidate control.

India, too, has enhanced its vigilance. Memories of the 2008 Mumbai terror attacks, launched from the sea, continue to drive security upgrades. The Border Security Force (BSF) has seized suspicious boats, intercepted smugglers, and even found abandoned vessels believed to be linked to infiltration attempts. During his Gujarat visit, Rajnath Singh inaugurated new security facilities, including a Tidal Independent Berthing Facility and a Joint Control Centre, aimed at integrating coastal defence operations.

Singh’s Sharp Warning to Islamabad

Addressing troops in Kutch, Singh reminded Pakistan of past wars, stating: “In 1965, the Indian Army reached Lahore. Pakistan should remember that the road to Karachi goes through Sir Creek.” He accused Islamabad of keeping the dispute alive with “malafide intentions”, pointing to the construction of military infrastructure as evidence. He added that any provocation would trigger decisive retaliation.

The minister’s visit coincided with Vijayadashami (Dussehra), where he performed Shastra Puja at Bhuj Military Station and observed joint-force exercises. Singh emphasised “jointness” between the Army, Navy, Air Force, and BSF, citing it as crucial to counter challenges. He also commended the success of Operation Sindoor, a recent rapid-response mission against Pakistani provocations.

Environmental and Political Complexities

Beyond military rivalry, the Sir Creek issue is entangled with ecological and treaty disputes. Pakistan’s Left Bank Outfall Drain (LBOD) canal, constructed between 1987 and 1997, channels saline water and industrial effluents into the sea via Sir Creek. While protecting the Indus’s freshwater, it causes flooding and soil damage on India’s side. New Delhi argues that this violates Article IV of the Indus Waters Treaty, adding another layer of discord.

The Roadblocks to Resolution

Despite several rounds of talks, Sir Creek remains unresolved because of sequencing disagreements. India prefers first finalising the maritime boundary in the Arabian Sea, which would clarify EEZ rights. Pakistan insists the territorial dispute over the creek itself must be settled first. The lack of consensus leaves the issue frozen, even as security risks escalate.

The Creek That Shapes the Future

Sir Creek may look like a strip of shifting marshland, but it holds the weight of history, strategy, and sovereignty. It symbolises the unfinished business of partition, the clash of legal interpretations, and the broader mistrust between India and Pakistan.

Rajnath Singh’s warning highlights not only India’s military resolve but also its frustration with Pakistan’s unwillingness to close the chapter. Yet, a long-term solution requires more than force—it demands diplomatic clarity, respect for historical agreements, and recognition of the economic and humanitarian stakes involved.

If left unresolved, Sir Creek will continue to fuel suspicion, militarisation, and hardship for ordinary fishermen. If settled wisely, however, it could transform from a symbol of rivalry into a channel of cooperation in South Asia’s most fragile frontier.

(With agency inputs)